- Expeditions

By Region

By Month

By Grade

By Height

- Treks

- UK & Alpine

- Schools

- Hire

- News

- Shop

Trip Report: Peak Lenin 2017 - Last one to the top

Peak Lenin – Last one to the top

12th August – 5th September 2017

Expedition Leader: Stu Peacock

One of the things I always tell my clients when climbing big mountains, is that it can be broken down as follows: 60% mental attitude, 30% physical effort and 10% luck. The luck being that the weather comes good at the right time, you are not ill and you’ve made all of your acclimatisation preparation. You can argue over the proportions I’ve mentioned above, but one assumption I have made is that you have the right equipment for the task ahead and that said equipment is with you and not stuck in Moscow because some official has not loaded it onto your onward flight, which in my case was to Osh for Peak Lenin!

In some respects it was probably a good thing that this happened to me and not one of the clients. At least I had the sense to keep to our company mantra of wearing my high altitude boots onto the plane, so as to keep them with me as part of my carry on. I’d also packed my down jacket in hand luggage along with my waterproof shells, mid layers and torch.

During the first day in Osh it slowly became clear, after many discussions with Moscow, that my baggage was not going to be sent on. This was almost the end of the trip for me before I had even started. It’s fair to say that Osh is not set up for any form of mountaineering, low or high altitude. However it is possible to buy base layers, walking boots and warmish trousers for high up on the mountain, from the bazar just down the road from the hotel.

By a stroke of luck the director of the agency we work with in Kyrgyzstan had a barrel full of kit at Peak Lenin base camp which contained the final missing pieces I needed in order to still be able to make a successful attempt on the summit. So for me personally and for the benefit of the team the show was back on the road!

Another major kit shortage was some of the group kit that I was bringing with me, namely: first aid supplies and communications equipment. Thankfully one of the team had worked as an expedition doctor and another member is a leader on student expeditions. So between the two we had sufficient first aid for the trip to continue. Our agent was also able to provide some hand-held radios and a Satellite phone, so all was in order to proceed.

Before we set off for Achik Tash (Peak Lenin Base Camp) the team got stuck in buying the necessary food items we would need for snacks and lunches on the mountain while I made my essential clothing purchases.

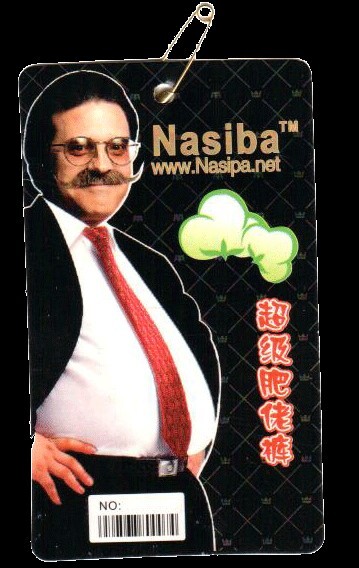

P.S. If you ever need good mountaineering boxer shorts don’t be put off by the labels

So once all the preparations were made it was with much relief that we set off on our 6 hour journey to Achik-Tash. The journey follows the road to the Tajik border, not that foreigners are allowed to cross there. The road goes over one high mountain pass, which is normally the main leg-stretching point and then eventually breaks off from the tarmac onto the final bumpy, dusty trail for the last hour to base camp.

From the road Peak Lenin was hidden in cloud, but by the time we reached Achik-Tash the clouds had parted and Lenin stood proud for all to see. There was a real buzz of excitement amongst the group, asking questions about the route on summit day, despite that part of the trip being a long way off. It’s an intoxicating atmosphere to be in, the team all giddy with the sense of adventure that lies ahead.

In base camp we met Andrey, the local guide working with our team, and I finally got the chance to check through the rest of the kit lent to me from our agent.

After acclimatising around base camp we move up to Advance Base Camp at 4400m, mules carrying our main luggage while we just carry our day packs. The next few days are critical in our acclimatisation plan because the jump up in height to the next camp on the mountain is significant. The temptation with many teams is to progress on the mountain itself and move up to Camp 2 at 5400. However the journey to Camp 2 is long and can be very hot, especially on the aptly named “Frying Pan” section of the glacier which can reach temperatures of 40C+.

- Peak Lenin Viewed from Jukhina Peak

We opted for climbing Jukhina Peak and camping on its summit. The ascent time is much shorter, approx. 2.5 hours verses the 6-7 hours needed to get to Camp 2. At 5137m it is only a couple of hundred metres lower than Camp 2. This allows us to conserve much more energy at this stage of the acclimatisation process.

Once completed it was time to move onto the mountain proper. It was noticeable that there were fewer people around at this stage of the season, certainly compared to July, and the Frying Pan was somewhat cooler than my previous experiences, albeit still hot. The condition of the glacier was pretty good compared to other seasons with the only crevasses that had to be negotiated requiring just a step across.

Camp 2 is not the best of places, lots of rubbish left by teams, which is really frustrating to see, but the camp is on rock so offers better insulation for sleeping and is well protected from objective dangers.

It snowed in the evening and overnight but thankfully the winds had scoured the key slopes we had to climb en-route to Camp 3. The distance is relatively short to Camp 3 but the final slope to Camp 3 makes you work hard. It was windy at Camp 3 and so once the tents were pitched everyone hunkered down for their first restless night at 6100m. Everything is an effort when camping at these heights. I woke in the early hours having drunk all my water still gasping for a drink. Your body is telling you to get up and make a drink but your mind is lethargic and just wants to rest. You have to fight it, so despite the internal protest I get up and melt snow, enough to quench my thirst and then some. Once satisfied that I’d drunk enough I grabbed the last few hours of slumber before we had to pack up and head back down to ABC for some well-earned R&R.

- View from Camp 3 to the Summit, seen on the left

While at ABC rumours were abound of several teams failing to reach the summit from Camp 3 due to strong winds and cold temperatures. Our intention was to install Camp 4 at 6400m, at the start of the plateau, providing winds allowed it. By shortening the summit day ascent it would give us the best chance of reaching the summit. Fortunately the winds were kind on our climb back up the mountain and we were able to pitch our tents at Camp 4. Several people made attempts on the summit the day we moved to Camp 4, but none reached the top. Once again the cold temperatures were forcing climbers to turn around.

On the 28th August, the morning of our summit bid we heard climbers walking past our tents around 2:30am. We were not due to leave until 4am, so still had some time to finish getting ready. The wind was up, higher than forecast and it was certainly cold once outside the comfort of the tent.

Route finding across the plateau was proving challenging in the darkness with the marker wands spread out further than your torch beam could reach due to the conditions, but once we reached the other side of the plateau the route finding became easier. At 6600m we met the climbers who had passed our tents earlier on. They had set off around midnight and had got too cold, so decided to head down. Looking back across the plateau and further down the mountain no other lights could be seen, so it appeared the final summit attempt of the season was down to us.

The air was bitingly cold and as we approached the steepening at 6700m the first blue streaks of dawn started to break through in the East. This is a pivotal time when climbing, especially if you are cold. If you can keep yourself going and keep yourself warm enough until the sun comes up then you find things start to get a bit easier. For me this is the best part of an ascent, being high on a mountain seeing the landscape literally come to life in front of you as the sun spreads its light over the world. The warmth and the fact you can see further than your torch beam kickstarts a surge of adrenalin. We’ve now climbed half the vertical ascent to the summit. Eating some snacks and getting some drink inside yourself gives you some of that much needed energy and a mental boost to get you back on your way.

Once past the steepening the route traverses round before dipping down on to the next plateau. At last we reach the final approach to the summit, but you have to be prepared for a couple of false summits along the way. Eventually out of the rock outcrops you start to pick out one formation that is more pronounced than the others. Unnatural features start to protrude that make you more aware that this could be the summit. As you get closer you can see artefacts that other people have left behind, confirming that you are indeed approaching the summit. With the last few steps the bust of Lenin draws into view along with prayer flags, placards, an ice axe and an assortment of other paraphernalia left to the mountain gods.

After our time enjoying the views and taking photos, it was time to retrace our steps down the mountain. It was only when we cleared down to Camp 3 that we realised everyone else had gone down. The same ghost town feeling presented itself at Camp 2 and at ABC. Artur, the camp manager, told us that everyone else had indeed left, all campsites dismantled, and we were the last to summit for the season. Our eyes the last to gaze upon Lenin perched on his rock at 7134m.

- Lenin looking out across the Pamirs

Read more about our Peak Lenin Expeditions

About Stu Peacock

Stu Peacock is a very experienced high altitude mountaineer who has been to the Summit of Everest, Broad Peak, Cho Oyu, Manaslu and climbed on K2. His other expeditions include: Ama Dablam, Annapurna IV, Peak Lenin, Aconcagua, Khan Tengri, Tien Shan Unclimbed, Korzhenevskaya, Himlung Himal, Baruntse, Mera & Island Peak, Alpamayo, Bolivian Peaks, Spantik, Carstensz Pyramid, Elbrus, MtArarat, Mexican Volcanoes, Mt Kenya and Kilimanjaro. He was the first Brit to summit Everest via the North Ridge 3 times and has climbed Everest from both the North & South sides.